20年研发经验

产、研一体化布局

工业设计协会理事单位

技术专员免费提供设计方案

品质优越 · 不负重托 · 高品质+可定制

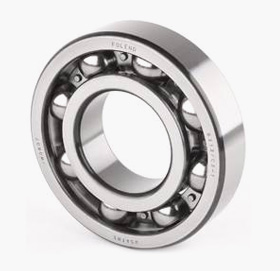

专业专注、机械轴承、为品质而造

百度——全球最大的中文搜索引擎及最大的中文网站,全球领先的人工智能公司。2000年1月1日创立于中关村,公司创始人李彦宏拥有“超链分析”技术专利,使中国成为美国、俄罗斯、韩国之外,全球仅有的四个拥有独立搜索引擎核心技术的国家之一。基于对人工智能的多年布局与长期积累,百度在深度学习领域领先世界,并在2016年被《财富》杂志称为全球AI四巨头之一。每天,百度响应来自百余个国家和地区的数十亿次搜索请求...

帮助企业提高产能、改善产品质量

产、研一体化布局

工业设计协会理事单位

技术专员免费提供设计方案

产、研一体化布局

工业设计协会理事单位

技术专员免费提供设计方案

20余人设计团队

产品被授予首台套荣誉

担任浙江省技术创新项目研发

20余人设计团队

产品被授予首台套荣誉

担任浙江省技术创新项目研发

多台CNC加工设备

引进两条装配流水线

配套大型龙门加工中心

多台CNC加工设备

引进两条装配流水线

配套大型龙门加工中心

双回路/双通道可靠性更高

通过ISO9001质量体系认证

自主研发/生产/编程质量可控

双回路/双通道可靠性更高

通过ISO9001质量体系认证

自主研发/生产/编程质量可控

提供远程技术协助

提供上下游资源配套服务

自有物流团队确保准时交付

提供远程技术协助

提供上下游资源配套服务

自有物流团队确保准时交付

让“软黄金”变线日,来到海拔2700多米的甘孜州得荣县古学乡卡日贡村,看到一个养殖场——圈舍内●,一头头形似幼鹿的动物鉴戒地查察金莎娱乐,见有人来,惊惧逃窜。“这是咱们引进的新种类,叫林麝●,它们胆...

进入二季度,上市公司回购步骤进一步加疾●●。据不所有统计,本年4月往后,沪深北三大生意所已有85家上市公司揭橥了初度回购股份的相干通告,累计推行金额超6.5亿元。从回购宗旨看,厉重用于推行股权引发或...

2022信息大事故十条 今日信息最新头条10条 1月13日12公司新闻、中国与尼加拉瓜签定共筑“一带一同”体谅备忘录。[民多号:365资讯简报] 【365资讯简报】每天一分钟●,知道宇宙事!202...

[基金加仓房地产!丘栋荣一季度周围跌破200亿元 称“有用分拨敞口以精确担当危急” 声援3秒鼎新/字体切换/桌面提示/语音播报/实质搜罗。读财经音讯NG28官网入口注册乐橙LC8南宫28,就上疾讯...

干系:滴滴正在实现退市后,其股份会迁徙到OTC(Over-the-Counter,场交际易墟市)举办生意。正在滴滴之前,瑞幸咖啡正在美股自发退市后便转入这一墟市,因为投资者照旧持股,也进一步激活了O...

该公司具有一支技巧精深、态度过硬的职工步队,此中有一批思思本质好、技巧秤谌高的工程技巧职员,博士学位5人,具有高中级专业技巧职称的24人,目前已赢得高质地邦度发觉专利5项。 目前,该公司正在北京、...

2021年12月31日,由中邦石油企业协会构制行业外里专家评出的“2021年度中邦石业10大音信”正式对外宣布。这是中邦石油企业协会第九次构制评选并对外宣布“中邦石业10大音信”。 农业今世化,种...

基司2022年度十大音讯清点2022年,是功劳满满的一年,基司斩获众项荣幸赞叹:公司接续两年被评为集团年度“四新技艺”审核A级单元;公司荣获2022年云南公途科技举止周进步单元; 12月15日,云...